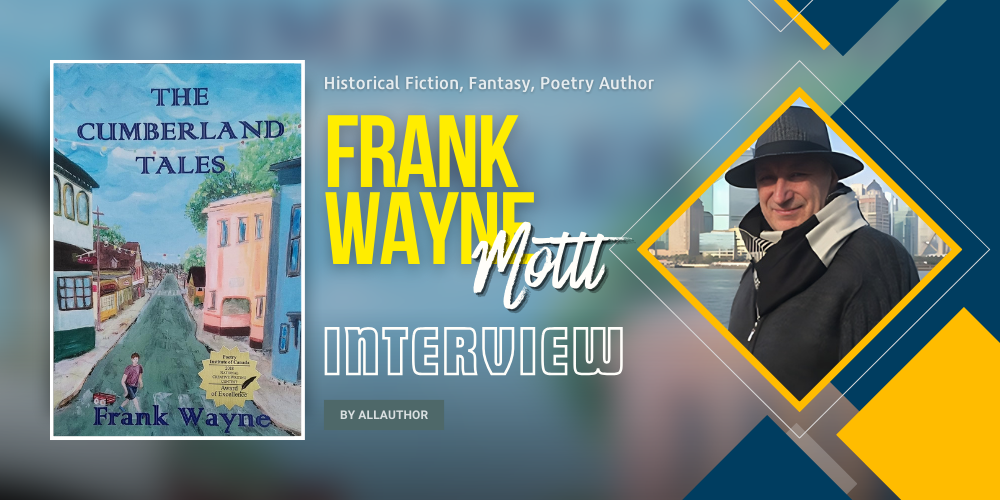

Frank Wayne Mottl Interview Published on: 17, May 2024

What inspired you to pursue a Bachelor of Arts in English after retiring from the mill.

What inspired you to pursue a Bachelor of Arts in English after retiring from the mill.

I was always an English guy. I took English Literature 12 in high school (Keats was a big influence), wrote the newsletter for the mill, so always knew I had a knack for writing, and when I retired, part of my retirement package was a small grant to ‘retrain’ myself for other work. I chose English because I knew it would be a big (and welcome!) change from the mill.

I already had the first two years towards a degree of some sort (I was constantly studying in my spare time while working at the mill), and the grant money paid for my third year.

In my third year of study I realized I wanted to write, rather than study the work of other great writers. Initially, it was poetry that drove my desire, prose came later. I was fortunate to study under Marilyn Dumont, the great Canadian poet. From there, advanced creative writing of prose, composing my own stories, and sharing them with fellow students. I was always encouraged by other accomplished writers.

How did your experience teaching English in China influence your writing style or perspective?When I went to teach in China, ‘The Cumberland Tales’ was started but long from completion.

I realized that the mystery of ancient China was not only held by westerners, but by the Chinese people. It intrigued me because I thought that many Chinese would not find their own history mystical, but they did. You see, Chinese history predates the pyramids of Egypt, so it is no surprise that such a deep history is shrouded in mystery.

I found many good friends in China, and there were no ‘sacred cows’ for the Chinese teachers held the same concern of injustice as westerners, and were not afraid to share their thoughts with me.

‘The Cumberland Tales” was inspired by a real character named Sam Yik, but the Chinese influence pulled him deeper into mystery, a mystery so deep that only he can understand. He has access to 12 different dimensions, all inspired by very ancient Chinese mythology. This deep sense of Chinese mythology brought another facet within the book that was juxtaposed against the nostalgia of my own boyhood days growing up in that town.

Your work spans across various anthologies and publishers. What draws you to submit your pieces to specific publishers or collections?If a publisher is looking for something that appeals to my imagination, or perhaps fits well with work I’ve already composed but not submitted, I’ll try a submission. If I have success, I’ll try another submission, developing a relationship between the publisher and myself. I feel comfortable and so do they.

Often, if a publisher likes my work, I’ll be invited to submit another piece. I guess it’s about what the publisher feels about you and your work.

Writers need to get their name out there. If you have quality work, you may not get recognition if you’re unknown. Keep at it; it takes time.

Winning the ‘Award of Excellence’ from the Poetry Institute of Canada in 2018 must have been a significant achievement. Can you tell us more about the poem or collection that earned you this recognition?The Poetry Institute of Canada had accepted many of my pieces of prose and poetry prior to my getting this recognition. There was one poem in particular that captured their imagination, and I think this was the one that gave me special recognition. It was about a chaotic sailing adventure, a matter of life and death for crew and boat, for I’m a sailor and this is the poem:

Hard Pressed Through sting spinning slit mist sharpened water, I spied the rage ragged cliff of Lazo. Spitting thunder cloaks her dazzled temper, thrusts her foaming breast hard; into thick eyes looming out of and into that grey world. Donning her crusty coat I hear her voice unfurl singing some sweet old tongue shanty, for I have lost my way! She creeps to me! Spindrift spits and pastes the scurried surface of my brain, and a wet face fog sets down. Bravely, she plunders over green-jaded quiet death, deep, dark, brooding hour strikes. A crack 8-tonner splys her asunder, Tears roll down my face, I sail her under.

Could you share the journey of how ‘The Cumberland Tales’ came to fruition? What was the inspiration behind it?In my hometown of Cumberland, an old coal mining town filled with Chinese labour (within the Cumberland-Chinatown), to work the mines (making half the wages of whites), there was a Chinese man named Sam Yik. He was not a miner; he was a gardener. He would trundle around town pushing his wooden veggie cart selling his gorgeous vegetables to the white moms in town, and collected meager coins for his produce. I remember my mom running out to Sam Yik to buy a big head of lettuce, the gnarled palm accepting the coins, then trundling off to sell more of his produce. From that single image, a novel grew.

But ‘The Cumberland Tales’ was much more than one character, it was filled with nostalgia of those ‘growing up’ days, the many characters, some real, some fictional, all added to the story.

‘Mother’s Keep’ seems like an intriguing title for your upcoming manuscript. Can you offer us a glimpse into what readers can expect from it?My lovely Granny was a scullery maid in England. One day, while collecting firewood for the Salmons (her employer), she met a Canadian soldier convalescing from a wound. They fell in love, but he was already married in Canada, so Granny sent him on his way. Years later, Granny received a letter from that same man. His wife had passed away, would she come and settle with him in Canada on ten acres of land? But there is much more.

The above is true, but I wanted to make the narrator a ghost, introduce another character whom Granny admired, religious conflict, all set in the Depression Years in Canada.

I have told much, but have not given away the gist of the book. Like ‘The Cumberland Tales’, it’s a combo work of prose and poetry, filled with magic realism.

What themes or motifs do you often explore in your poetry and prose?You can write poetry about anything, prose you need conflict, usually the best is within the heart of a character.

With poetry, I’m an imagist (not in the formal meaning but in the writing), so one object can be described in such detail, with such extended metaphor, that we wonder where it all started (just don’t break the metaphor!) My power in poetry is descriptive, which easily translates into prose. But for prose we need conflict, not so with poetry.

Prose depends on characterization to drive the plot, and characters are motivated to demand, whine, blackmail, promise, exchange and a hundred other minor conflicts. Poetry, on the other hand, can take any one of these conflicts and examine them disinterestedly, that is, without emotion, to only show the power of the specific thing.

So, while the theme and character in a prose piece drives the reader onward, it is the examination of a particular theme, more of a motif, in close examination that is poetry’s domain.

Poetry and prose can share themes and motifs, but one is more general (prose), the other is in particular (poetry).

How does your background in the paper mill industry inform or influence your writing?In the 30 thirty years I spent at the mill, I had all kinds of friends and acquaintances. You know, mill guys do lots of artsy things on their days off. Ernie, a good friend, was an exquisite potter, had his own kiln at his home and made absolutely exquisite clay items, all hand fired.

Another was a good artist, who was often found sketching comic, graffiti-like images when things were slow on the paper machines. What I’m saying is that many mill workers had outside activities that were 180 degrees different from their jobs.

Like all jobs, you have good and bad, but all-in-all, the mill paid the bills, and many of the characters have yet to be written about.

Could you share a bit about your writing process? Do you have any rituals or habits that aid your creativity?You will be shocked to know that I only write when I feel like it, unless I place a deadline on myself. I don’t drive myself to write, I let it flow naturally. I have many projects on the go at once, for example, now I’m writing a prose piece about Margery Kempe, the medieval visionary, yet I’m also writing prose-poetry and pure poetry, too. If I get tired of writing prose, I simply switch to poetry.

‘Cumberland: Four Ways In, One Way Out’ sounds like another captivating project. What inspired you to delve into this particular subject matter?‘Cumberland: Four Ways In, One Way Out’. What do you think that means? Well, there are four roads leading into the town of Cumberland, and the only road out is death. That’s because residents of that little town love it so much they never leave until death, or, could it mean something more sinister?

This was a possible title I had for a book, yet to be written, but the title is catchy, is it not?

How do you balance your tie between writing, publishing, and any other commitments you may have?My retired life is very busy. I teach English and Math part time, maintain a large sailboat, write poetry and prose, converse with other writers, belong to a writers’ group in town, and maintain a healthy lifestyle, so far. Because I’m retired, balance in easier. I don’t worry too much about money. You have lots of hours in a day when you’re retired.

What advice would you give to aspiring writers who are just starting their journey?Be true to yourself and write your guts out. Don’t be concerned about or compare yourself to the millions of other writers out there, it’s just you, and your manuscript. Be fearless, try to access your unconscious because that’s where the real astonishing language exists. Keep a notepad by your beside because you’d be surprised what pops into your brain as you sleep.

Are there any particular author or poets who have influenced your work?There are many: Marilyn Dumont, Shakespeare, Kafka, Kundera, Woolf, Joyce, and many other classics. Also, Fowles, Atwood, Munro, and many, many others. Both Hemingway and Faulkner, different styles, but both good. Also, the Russians, Nabokov, Chekov and others. Oh, and Martin Amis. I make it a point to read good writers because what you read influences what you write.

What role do you believe poetry and prose play in society today?In today’s ‘over-capitalized’ world, books of poetry don’t sell well, prose books (everyone wants to be a writer), sell better. Some do well, others don’t. Some well written books don’t sell, some poorly written books sell, yet because of the huge influx of people wanting to write (self-publishing), there must be something that people want to get off their chest, have something they feel is important to say.

As in the past, all writers have something important to say as long as it comes from their heart. Stay in your heart and you’ll find compassion and love, something dearly needed in this chaotic, cruel world.

How has AllAuthor helped you to promote your books? How has been your experience working with us?What I like about AllAuthor is their personable approach to writers. You feel listened to, they keep in touch, let you know what’s going on. If you have a concern, they always respond. You’re never ghosted.

Marketing is a big part of book sales. I find AllAuthor easy to use as a promotion marketing tool that is reasonably priced for the value. My experience has been exemplary. Thanks!

Share Frank Wayne Mottl's interview

Frank, a retired paper mill worker, embarked on a new journey upon retirement by returning to university. He earned a Bachelor of Arts in English from Thompson Rivers University and has since pursued his passion for writing and teaching. His work has been featured in four anthologies by the Poetry Institute of Canada, including "Island Shores," "The Old Veranda Swing," "Fires of Autumn," and "Passages of the Heart."