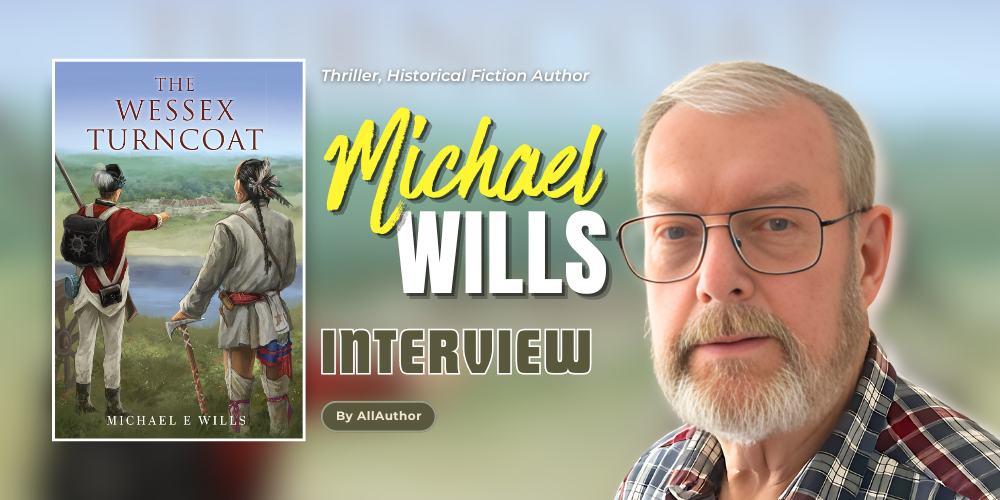

Michael E Wills Interview Published on: 13, May 2024

What are some early childhood experiences you had that really shaped the way you are today?

What are some early childhood experiences you had that really shaped the way you are today?

When I was a child, we had no TV. In fact the first Time I saw a television was around about 1953 when my grandfather, a man who loved gadgets, bought a television set. It was wooden box with a screen measuring about 25 cms square! The picture was so small that the manufacturer supplied a large magnifying glass to put in front of the screen! So, as a young boy, like most of my generation, I was an avid radio listener and book reader. Both of these sources were great for developing my imagination and they also formed in me a love of telling stories inspired by what I heard and read.

What inspired you to delve into historical fiction, particularly exploring diverse periods such as the Late Stone Age and the Second World War?I have always been intrigued by history, not least because my childhood home was within sight of a medieval castle, Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight. To my mother’s horror, I developed a habit of collecting dusty historical bits and pieces. I often went to what were called, “jumble sales”. These were events when people could sell items they didn’t want. My collection ranged from stone age arrow heads, to Second World War helmets and from old coins to a real 18th century musket. These items fired my imagination!

Your works span a wide range of historical eras. How do you decide which time periods to explore in your writing?I think it is true to say that the initial stimulus, the thing that gave the spark, for writing all of my books came from seeing an object or a place. In many cases I was lucky enough to experience this stimulus in reality, This meant, for example, that when I saw some of the newly discovered skeletons of Viking warriors in a mass grave near where I was once working, my imagination was fired to find out more about who they were and how they came to be buried just in that place. It led to me writing my first book, “Finn’s Fate”.

A visit to the Redcoat Museum in my hometown, Salisbury, led me to a fascination with the American War of Independence and writing “The Wessex Turncoat”.

Watching a guide show how tell-tale signs on the bones of a stone age man could help to build the story of how had lived and died, made me want to tell his story in “Izar, the Amesbury Archer”.

In retrospect, I realise that this way of writing, varying the historical period according to my own interests, did not make good commercial sense, in general, the most successful historical fiction writers seem to write about one or perhaps two particular periods.

Can you share your research process when developing the historical backdrop for your novels?Research is absolutely essential for historic fiction, but in fact I find it the most enjoyable aspect of the writing process. These days, it is possible to do a lot of the research in an armchair looking at a computer, but I believe in the importance of trying to experience the environments, the scenes, the climate and in some cases the diets of the people I write about. For example, in “Finn’s Fate”, archaeological science established that three of the skeletons found were those of men born north of the Arctic Circle. I decided to go there to see what I could find out about the history of the Sami people. But first, I wanted to experience the voyage which Vikings would have had to make to raid the shores of England. So, together with my wife I sailed to Sweden in a sailboat. I can guarantee that the description of North Sea storms in the book do faithfully reflect reality! Then we visited boat yards where exact replicas of Viking ships are still made, to learn about them. It was also possible to see reenactments of battles and to sample types of food which would have been eaten a thousand years ago. All this to make the story as authentic as possible.

Your series for children focuses on evacuees in the Second World War. What motivated you to write for this specific audience and about this particular aspect of history?I am a veteran writer! I was actually alive in the final years of the Second World War. My grandchildren have many times asked me questions about that terrible time. They all have to study the period as part of their history lessons. I quickly realised that I was a sort of living history resource!

I decided that it would be a good idea to write down some facts about the war, but I did not want to write a non-fiction history book. I am a storyteller. I decided to write three exciting stories, partly based on fact, each with small sections of “True Facts” in text boxes relating to particular parts of the stories. In this way, children would get the real history through reading a fiction adventure story.

I was aware that during the war, hundreds of thousands of children were moved from cities to smaller towns in the countryside for their safety. They went to stay with complete strangers, they were known as “evacuees”. I wanted to tell their story too, so the main characters in the stories were evacuees.

How do you balance historical accuracy with creative storytelling? Are there specific challenges you face when writing about real historical events and figures?There is a huge difference between writing about the stone age and for example, the American War of Independence. In the former case, there are no contemporary written facts and the only background is archaeological. Though this is often open to differences of academic opinion. Thus, writing about this period is to some extent like painting on a blank canvas. However, in the case of my book “The Wessex Turncoat”, every minor skirmish, let alone battles, is documented in army records. I had to do a huge amount of reading to ensure that my story could not be challenged as regards the factual content. I was very fortunate too to be invited to see a full-scale re-enactment of the Battle of Saratoga in USA. There I learnt a great deal about the different uniforms used by the American combatants in 1777, when they were fighting the British.

Could you discuss any memorable or surprising discoveries you made during your research that significantly influenced your storytelling?When doing research in Scandinavia, I have formed a fascination with rune stones. These are usually large stone blocks on which a “rune master” has chiselled a message of some sort, often in the form of a memorial to someone. They are decorated with stunning designs of writhing snakes and mythological figures. Fortunately, these monuments are, these days, carefully preserved and often there is a modern translation of the message carved in the runic alphabet, by the side of them.

On a drive in the country, just south of Stockholm airport, I stopped to look at a picturesque ancient village church. To my surprise there were two runestones in front of the church. The one which really caught my attention had a thousand year-old inscription which was translated to, “Ulf of Borresta gained a tribute in England three times. Once under Toste, once under Thorkell, and once under Knut.“

I quickly realised that the inscription told of a local man who had taken part in Viking raids on England, three times under different commanders and had been paid silver each time, extorted from the English king. What a story! It became my fourteenth book, “For the Want of Silver”!

In your opinion, what role does historical fiction play in educating readers about the past?I have a strong belief in the importance of a knowledge of history. However, a study of it can, to many, be tedious and uninteresting. Historical fiction can bring the subject alive and with a good story, become a page turner!

The Late Stone Age might be a less explored period in historical fiction. What drew you to this era, and how did you approach bringing it to life in your writing?I am fortunate enough to live within a short distance of Stonehenge. However, such familiarity with an ancient monument does not necessarily mean that it is appreciated. It was first when, as a teacher, I had to introduce students to the massive circle of stones, and thus be well informed about it, that I began to appreciate the fascination of the extraordinary construction. This and easy access to a vast number of other stone age burials and artifacts in the area heightened my interest in the period, an interest which drew me to the skeleton of the Amesbury Archer in the local museum.

I found it intriguing to consider how people of this period lived and communicated. One could not even take basic things for granted. For example, did they have names? How did they measure distance? (A fundamental requirement when building Stonehenge!).

Your characters, like Izar and The Amesbury Archer, come from different time periods. How do you develop and breathe life into characters from such diverse historical backgrounds?The most important thing is to make the characters, in particular the main protagonist, believable. The reader must be given enough detail of what a person looks like, thinks like and acts like, so that a mental picture can be drawn. However, enough space must be left for the reader to use her/his imagination.

The latter is also true about the conclusions a reader might make about how a protagonist would act. The last page of “The Wessex Turncoat” leaves the reader to make up her/his mind about what decision the main character makes about a life choice. It is really interesting to hear from readers what decision they think he made. A conversation about this with a taxi driver who had read the book, served to shorten an otherwise tedious journey, as he tried to convince me what the man would do!

Do you have a favourite historical period or character that you've written about? If so, what makes them stand out to you?Yes, my favourite character is Izar. His skeleton tells us that he had a physical handicap and would have had difficulty in walking. Yet research on his bones show that although he was born in the region of the Alps he somehow managed to travel, almost certainly on foot, to the area of Stonehenge. Through his life in what is now England, he did something which gained him such respect that he was buried in a fine grave together with over a hundred objects, including the oldest golden items every found in this country. What a man! What a mystery!

How do you weave personal stories and emotions into the larger historical context in your novels?This was a puzzle to me in the case of “The Wessex Turncoat”. I wanted to write a story, not one about the grand events of the War of Independence, not about the generals and not about the supreme optimism of an English king. I wanted to tell the way it was for the men who crossed an ocean, fought a canny enemy and, ill-equipped, survived a Canadian winter, all for a lost cause. I decided to tell the story through the eyes and experiences of a simple country boy who, very unwillingly, is forced to join the British army. He grows up as the story unfolds. He endures the savagery of army discipline, the euphoria of victory and the sorrow of defeat, but ultimately, the question is, will he ever see his Wessex village again?

Writing for children requires a unique approach. How do you adapt your writing style and themes to engage younger readers while still addressing the historical realities of war?Yes, writing for children does require a different approach. I had the advantage of having once been a teacher. I am sure I am not the only one who has at some time taught an unsuccessful lesson because of assuming that what interests the teacher would interest the children.

I found that in my teaching and later in my writing much depends on how facts are presented. In the case of my war stories, I am careful to avoid the awfulness of war in the stories, but the text boxes do give some background to what was really happening at the time the children’s story was developing.

One thing which I think is very difficult with children’s books is the filtering of language. It is important for children to build their vocabulary through reading. However, I have seen that including too many unusual, or perhaps “new” words, can turn a reader off and cause them to give up. It is a difficult balance!

Can you give us a sneak peek into any upcoming projects or stories you're currently working on? Any hints or details you can share?My great uncle was the captain on one of the “small ships” which rescued over 300,000 British soldiers from the shore of Dunkirk, in France, in 1940. There is a rumour that a sixteen year-old boy stowed away on his ship, not knowing where it was going. This is his story!

How has your experience of being associated with AllAuthor been?I appreciate being a member of the AllAuthor community of authors. Writing is a lonely occupation and its good to be in association with others doing the same thing.

The mock-up banners provided for my books are really useful and certainly better than anything I could produce myself.

Share Michael E Wills's interview

Michael Wills is a semi-retired writer residing in the serene landscapes of southern England. Specializing in historical fiction, Michael takes readers on captivating journeys through time, weaving tales that span from the Late Stone Age, as seen in work like "Izar, Amesbury Archer," to heartfelt stories centered around evacuees during the tumultuous era of the Second World War.