Timothy Cooper Interview Published on: 10, Jul 2018

You were born in Los Angeles, California and grew up in Washington, DC. How do you think these places have affected what you write and how you write about it?

You were born in Los Angeles, California and grew up in Washington, DC. How do you think these places have affected what you write and how you write about it?

The West Coast taught me that humor was the best antidote for all that ails Washington politics, if not, well, world politics. So for me, the West Coast was where I first became wholly aware of just how much humor could address and highlight social justice issues because I was reading rivers of Mark Twain back then, back in the 1970s, when I was living in LA and attending a graduate film program and learning to appreciate how Twain exposed the horrors of slavery in the context of a rather humorous novel, “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.” So it may have been Mr. Twain’s brilliant works, more than the lightness of LA or the smiling California sunshine and coastlines that gave me my love of humor. What’s certain is that humor has provided me with a lifelong antitoxin for the insufficiencies and hypocrisies of politics. Better than the most delicious wine in the deepest French wine cellar on the oldest winery in the Loire Valley.

On the bright side, however, the East Coast taught me that politics is the steam engine for arriving at the practical, though a gentleman’s game it is most definitely not. Certainly it may try to masquerade itself as one, but it’s more like a Game of Thrones. Interesting to watch and perhaps even participate in for a time, but ultimately, let’s face it, it’s a zero-sum game, like dens of hungry tigers locked in a cage at past meal time. So to write lovingly about politics today requires the salve of humor, the balm of comedy, to get at the truth.

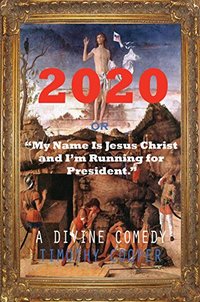

So my fiction straddles between the influences of both coasts— and in “2020” in particular. This is a novel where politics and humor collide—meet head-on and crash into each other unrelentingly because it’s a novel about religion’s role in America politics (and even world politics) and what Christ might have to say about that should he return to Earth one day as prophesied.

I would think that the evangelists, among others, would have a keen interest that that which is why I would very much encourage them to buy my novel to get a sneak preview about the Good News. So I would be so bold as to say that “2020” is in fact about politics, and is in fact about religion, it’s also simultaneously a prophetic novel of sorts because not only did it accurately predict the coming of the Obama era, but it also foresaw the smoky dawn of the Trump era. (www.Jesus2020.net).

So, in a sense, “2020” is more than a mere novel. It’s like a Gospel According to Satire or the Comedy of Revelation or even the Non-Apocalypse of John. Take your pick. Any which way, it’s predictive.

But on a more serious note, it’s the definitive novel about politics in the 21st century. How do I know this? Because it tells it like it’s going to happen. Christ will return to light the torch of justice and try to rid the world of a flimflam man who claims to be—yes, him. So who will win? Well, God only knows.

Tell us how you came up with the plot for 2020 or My Name is Jesus and I'm running for President?For me, writing fiction is akin to scanning the oceans at night with a flashlight, looking for the thin line of a darkened horizon. Over the months and years, you search and search until miraculously—or not, it comes to you. That’s the way it is for me as I develop plot. It’s a divined process of discovery, and more often than not, through the grand surprise of intuition.

And of course, intuition is helped considerably by the number of drafts you write. For “2020” I wrote six, or was it seven? It was only after that I finally cracked the novel’s tone and content, felt confident that every last bit of humor had the right amount of bounce, believed there was a true consistency of tone, and that the hilarity of my character’s voices hit the mark time and time again. And what a relief that was, too, because you never really know whether you’re going to crack it or not, that is, until it’s done. What’s that expression? It seems impossible until it’s done. Until you hear each note of your anthem played in the proper key, and with the exactly right emphasis of phrasing and, of course, to a flawless beat, you never know whether it’s going to come out alright in the end. It’s like holding your breath underwater for years and years, waiting, hoping, praying for everything to work out and be put exactly right.

How does this happen? Where does plot and character come from? Don’t know. It all seems like a fairly random gift, coming out of the unconscious. The voice inside you’ve never heard before, a release of part of your soul that you’ve never known before. In this sense, the plot for “2020” was a wholly organic development, scooped up from unchartered water. How its plot weaves, how its celebrity characters take stage, how its multiplicity of themes unfold, it’s all organic and come from an unreasonable faith that it will all work out in the end, like I said.

It’s the mystery of making vegetable wraps in writing. You mix up a batch of fresh vegetables; you blend in some dressings, origins unknown; then you wrap them into a wheat flour wrap that’s been warmed on a toasty grill, and voila: it’s done. But it’s not the specific ingredients that tastes so good. It’s the mystic blending of all of them rolled into one: Plot, character, theme, even vision. So that’s how I get there.

Some writers plot out their storylines meticulously, and before they write many words. And I say, good on them. That’s admirable, and likely the exact right approach. Certainly, they encourage that approach in screenwriting class and probably at the Iowa Writing Conferences, too. But I love the purely organic approach, for better or for worse. That’s to say, I love surprises, and being blindsided by, as always, the unexpected. I live for those cool, hyper-unusual moments when your mind somehow or other breaks through its befuddled confusion and cyclonic distraction and dips into what I think of as the silent eye of a creative hurricane, where unique light forms, unearthly, intense, and changes everything inside. For me, that’s the thrill. Those moments. You can’t anticipate them. They just happen. Or not. So, yes, I probably lose something not doing 2x5 cards on a wall beforehand; but I hope I reach a more unique place than I would have otherwise if I didn’t take the chance of stumbling into a feverish, unrelenting word dream.

What is the relevance of the title of your book?Well, with a high degree of accuracy, and 99.999% certainty, the title of my novel predicts about when Christ will return to Earth. Not many novel titles can make that boast, which is reason enough for readers to read it. The novel itself tells the story of how, why and where Christ arrives and what he does when he gets here.

Now don’t get me wrong, because I’m not in any kind of competition with America’s evangelists on the issue of predictions. We all know that generally speaking evangelists make their own predictions of this sort, so I’m not trying to impinge on their traditional territory, but so far none of them have gotten the date right, so I think I’m entitled to my own shot, don’t you? And I’d be happy to share the credit for an accurate prediction, should I get it right. Fair’s fair. They’ve been in this business for a long, long time. I’m a relative newcomer, at best.

Politics is a controversial genre to write on. Were there any challenges that you faced while writing something like 2020 or My Name is Jesus and I'm Running for President?Well, first of all, most people take their politics very seriously, so this is a novel that makes light of politics or at least the presidential campaign process. So that’s a challenge: the subject matter itself and the partisan nature of the story’s structure. But this novel is about how I see American politics, how I see the American two-party system, and how I see the influences of the day affecting the political landscape of the country.

Now I know that I probably should have written a requiem, instead of a comedy, at the state of political combat today. But my good mother raised me as an optimist, so I chose to bury my overt cynicisms and feast on the more comedic parts of politics, a sort of divine sustenance. Naturally, this was challenging, at first. How does one take a serious subject and turn it on its head? Trying to make readable literature out of a running, epic political commentary requires dedication and a certain raw, unflappable nerve. But that’s what I tried to do. Success or not. The fact that the country has yet to recognize my novel for what it obviously is--the Second Coming of American Literature, camouflaged as political satire, is most unfortunate; but hey, who am I to second-guess the country’s readership? Suffice to say, writing politics as satire in the age of Trump and Pence is a minefield, but needed now, much, much more than ever.

How have you handled any backlash received from supporters of a political party or figure?Well, I think it goes something like this: I suspect that my one-star reviews, given effortlessly without comment, are, shall we say… being passed along more as a non-literary judgment by any Republican or evangelical readers. And that’s okay. No problem. But I suspect that they may never have cracked open the book, let alone read its 544 pages. And then, of course, the 5-star reviews may likely be coming from Democrats or even a more liberal strain of Christians. So there’s that! The other side of the equation. Nothing wrong with that either. But I have to say that those readers who do comment on say, Goodreads, more often than not, tend to point out that the novel is not at all heretical and yes, very respectful of the novel’s main character—Christ. One reviewer, in particular, nailed it I thought. She said that Christ as a character was neither a Democrat nor a Republican. That he was, in a sense, a living Christ! Or that’s how I interpreted what she was saying. And of course, that’s precisely how I tried to convey him, write him, make him breathe on the page. Which is not an easy thing to do.

So, in this sense, the novel attempts to be above and beyond politics. It makes an effort to re-tell the old story of the battle between good and evil by using humor to highlight a fantastical tale of Christ’s Second Coming.

So be there backlash or not, the intention of the book is to also have a serious look at what Christ’s attitudes might be if he were to land at Sunset Boulevard and Vine one day in the not-too-distant future.

Mike Pence should read this book. And I’d like Donald Trump to read it too, but I know he doesn’t read much, so that’s out. Still, evangelists, mainstream Christians, Jews and atheists, there’s something in it for everyone, so they should consider having a serious look.

Kirkus Reviews said that “2020” reflected the times we’re living in and was tailor-made for readers of political fiction. And Kirkus is right. In part, the novel addresses the chaos in American politics caused by the influence of religion in our two-party, acrimonious politics. This is what some readers don’t get it. But I have faith that they eventually will. One reader, for instance, said that the book “will be considered a great book one day, if people ever understand it.” Maybe they will and maybe they won’t. But I’m hoping that reader is right, that over time the novel will gain more and more altitude, especially once readers give it a chance and stop reacting viscerally to its title and its audacious but respectful premise. Perhaps that will happen one day. Who knows? Perhaps after I’m long gone, “2020 or My Name is Jesus Christ and I’m Running for President” will undergo a kind of resurrection in readership. Or put another way, experience its own kind of literary Rapture whereby it will be lifted into the Heavens of well-regarded 21st Century fiction because, well, miracles do happen!

Does it bother you that when you club religion and contemporary politics, you might end up hurting people's sentiments? How do you try to avoid it?I don’t. I seize tomorrow today and write what compels me. Why else would one do it? Readers and reviewers have their own space in which to respond. But by their very nature writers are meant to be provocative, daring, probing, and all sides of controversial. But having said that, I definitely wouldn’t say that “2020” should in any way offend or rub up against anyone’s religious sentiments. Not in the least. On the contrary, it’s an original, thoughtful story about the reaffirmation of faith and the engines of peace. I mean, how much more religious, by way of themes, can you get than that? However, and this is entirely deliberate, and where any controversy may come in, the key message of the novel is about the separation of religion from secular politics. In America, this shouldn’t be a controversial concept. Not even close. But today, evidently, it is getting to be more and more so. Just look where we are. Christian fundamentalists, evangelists, pretty much insist on just the opposite. But I don’t think that Christ, were he to return to Earth, would stand for it. Not in the least. He’d see it as a perversion of his simple message: Love they neighbor as thyself. And he certainly wouldn’t take kindly to evangelists trumpeting his name in support of much other than that.

And remember, if history teaches us anything it’s that religion shoehorned into secular politics is akin to mixing bottles of kerosene with packs of lighted matches.

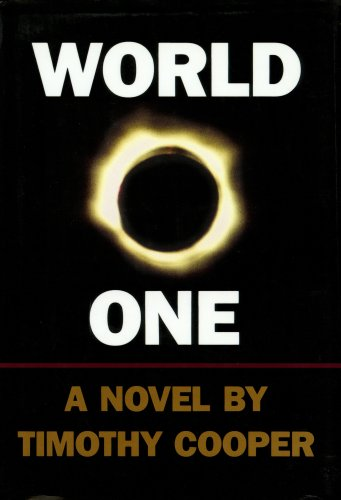

Your first book "The World One" is also on the lines of politics. What is it about politics that attracts you so much to the genre?Well, “World One” is part of a category of fiction I call “nuclear” fiction. It’s an important form of niche writing, for sure, and overflows with some fairly hefty 20th Century doomsday classics, such as Nevil Shute’s “On the Beach”, Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker, and Peter George’s, “Red Alert”, which was famously turned into the Stanley Kubrick movie classic, “Dr. Strangelove”.

If ever there was an end-of-the-world story suffused with radioactive humor and satirical fallout, that’s the one.

So yes, “World One” was my effort to contribute to that genre. The novel is told as a series of stories by survivors of a past nuclear holocaust, and where Washington, DC is now covered in high waters and only patches of civilization remain and the human-dogs—post apocalypse anarchists—abound, further threatening the world’s incipient recovery. It paints a vision of a future world society finally won by its resistance to lawlessness, chaos and acts of war. And as the stories of war and peace continue the human-dogs are tamed…

“World One” was written during the Regan Administration, at a time when fear of a nuclear showdown between the U.S. and the Soviets was running at a fever pitch. So it’s a bit of a period piece, part prophesy, part aspirational, and part flat-out hope that better ages for humanity lie ahead.

But, of course, how we get there is anyone’s guess. “World One” offers some thoughts about that, and that’s why I wrote it in the first place. So absolutely, it’s a genuinely political novel and I love the art of the possible—politics.

Emery Reeves’ “The Anatomy of Peace” inspired the writing of “World One”. If you don’t know about Emery Reeves, he’s definitely worth a read. He was quite an effective advocate for some form of global federalism. Today, of course, world federalism of whatever kind is not exactly a trendy topic, especially not in these weird and toxic days of hysterical anti-globalism. But there it is. So to get away as far as possible from these strange days, “World One” paints a compelling tapestry about what I believe will be tomorrow’s tomorrow tomorrow… (https://www.amazon.com/World-One-Timothy-Cooper/dp/0961991402)

Let's go back to the beginning of it all. When was the first time you realized you wanted to be a writer? What inspired you?In film school, at the AFI, Center for Advanced Film Studies, and at the age of 19. In a cyclone of hyper-awe about the possibilities of the power of writing, I began writing my first solo screenplay in a 6x6 room down in the basement of a Laurel Canyon ranch house, which was nicely nestled into the dry Hollywood hills. And as I recall was situated below a screaming rock band recording studio which, as you’d expect, recorded late into night, most nights. These bands were not timid about broadcasting their music. It was loud. It was rock. And there was no mute button. So that period tested my powers of concentration. But it got me off to a good start.

I began my writing on a 1920s Underwood typewriter. The kind that produces painful callouses on each of your fingertips because you have to strike each key all too aggressively to get it to print right. And I set out to write a screenplay about the end of the 1960s, about the demise of the Beatles generation, its last hours, as it were, and to tell a narrative about how greed undermined all those friendships that took place during that extraordinary time. But more than that it was a story about how the collective ideals of the ‘60s were disappearing, about how the romanticism of life lived as a collective idea was beginning to fade and overtaken by the reassertion of America’s culture of individualism and a return of Existentialism—that the individual was the master of his or her own fate.

For inspiration, I was exposed to some of Hollywood’s greatest screenwriters as part of my studies at the AFI. Screenwriters like Robert Riskin, John Houston, Orson Welles, Herman Mankiewicz, Joseph Mankiewicz, Robert Bolt, Paddy Chayefsky, Robert Towne, Francois Truffaut, Ingmar Bergman, Federico Fellini, Ernest Lehman, and John Steinbeck, among others.

All the while I was feasting on some of America’s greatest novelists: Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Faulkner, and Joyce, as well as genre writers such as Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett. It was a pretty good mix of romantics and surrealists, gumshoes and poets. But, my favorite, of course, was F. Scott Fitzgerald. He’s pure romance, with a sprinkling of tragic and poignant, if not sweet. I mean, how do you not love—no, glory in—his last, unfinished novel, “The Last Tycoon”?

Its first paragraph is a lesson in understatement: “Though I haven’t ever been on the screen I was brought up in pictures. Rudolph Valentino came to my fifth birthday party—or so I was told. I put this down only to indicate that even before the age of reason I was in a position to watch the wheels go round.”

Fitzgerald completed only about 70,000 words of his intended 150,000-word novel. Nevertheless, what is there is certainly as good as anything he wrote in “The Great Gatsby”. So the question for me was how could I not try to write with literary influences such as these writ large on my horizon? With these legendary voices whispering back and forth in my head, calling, challenging, exciting, demanding.

You contribute a lot to works regarding human rights and peace. How important do you think it is for people to realize these global problems and do something about it.Internationally recognized human rights define the very architecture of a universal code of conduct, so ideally a working knowledge about the scope and breadth of what human rights actually are should, in my opinion, be a required teaching in grade schools, in high schools and, of course, at the college level.

Why? Because human rights represent core values as well as key obligations about how governments should and must treat their citizens. So it doesn’t get a whole lot more important than that. In a word, they’re about dignity, about promoting and protecting human dignity.

Essentially, those human rights set down in various human rights treaties define both the rights and obligations of citizens the world over. And it is in the recognition of and of course the enforcement of these rights that lies, perhaps, the world’s best hope for achieving a more civilized world society. Human rights have the potential for increasing justice, for protecting against governmental abuse, to achieving something like equal rights for all.

That’s a fairly honorable ambition. And they can even be used to promote peace, which elevates them to a whole new level of potential.

So I’d say that human rights are a vivid and creative area of activism. They’re a tool to be used in any and all parts of the world to advance civil and political rights for everyone. The immutable concept here is that a violation of rights anywhere is a violation of rights everywhere. So, yes, we should all be concerned about the promotion and protection of other people’s rights and take time out to get involved to whatever extent we can to helping to defend them, because it’s simply the neighborly thing to do. And on a planet this small and this interconnected and this volatile, it’s at minimum the right thing to do.

You are also a pianist. Was that your first career choice? What are your other passions apart from music and writing?I started teaching myself piano at the AFI in Los Angeles on a gorgeous Mason & Hamlin 1930s piano. Oh, was this a beautiful baby grand piano. Such a rich, round tone-- such a dense, hypnotic sound. And then I just doggedly kept at it. I’d search near and far for pianos. There was this Steinway piano at St. Albans Parish in Washington, DC that I’d play as often as I could, until, of course, Norman Scribner, the former Washington Choral Society music director, banned me, for reasons best understood by him! But naturally his banishment didn’t dissuade me, fro seeking out other pianos at college campuses or wherever, not in the least. Until such time as I finally got ahold of a 9-foot Baldwin concert grand piano, and started recording CDs. With two U87 Neuman microphones, no less. Classic beauties.

My last CD, “Global Skies”, put out at the end of last year, climbed into the Top Ten of the Zone Music Charts, and has evidently stayed in the Top 100 for pretty much the last six months. (www.newpianoage.com) So for me my adventures into recording land of original piano music have been gratifying in ways I could have never imagined, because the language of music is absolutely extraordinary—like nothing else. It can take you into the well of your soul at any time. It can transport you across horizons you’ve never known before and may never see again. You can find yourself or lose yourself there, in melody, in chords, in the composition as a whole. Individuality translates into universality. It can be one and the same. So what’s not to love?

I’d like to think that I have a dozen or more CDs stuffed somewhere inside me, scrambling to get out. So hopefully they will. Am experimenting with a new musical concept called New Age Amalgam Jazz. Sometimes I can hear, sometimes I can actually play it, so I might actually be able to do something with it in time. My dad was an accomplished jazz pianist and a big fan of Bill Evans, the stellar pianist. So if I get something down that’s any good, I’ll dedicate that new CD, which will try to break new ground, to my dad.

You are a professional photographer. How different do you think writing and photography are, as art forms? Which one do you love more?Hmmmh, great question, with no easy answer. That’s a bit it’s like asking which one of your two children do you love more? Ultimately, it’s impossible to say.

That’s because when you’re in the zone with your writing, with your photography, you get to a place that seems, at least for those fleeting moments, like a hard-won nirvana, like the best of all possible worlds—because each transports. And that’s what it’s about, isn’t it? A conveyance into a space beyond where you presently stand. So long as they both transport, they both offer that very exceptional experience. That’s what it’s all about, no? The grasp at art. (https://www.flickr.com/photos/138434107@N05/40162595731/in/album-72157692440574254/)

Coming back to politics, do you think the youth can play a huge role in changing the scene of world politics? How?Well, let’s hope so, most emphatically. They certainly did in the Sixties, so why not today? And they have every incentive; it’s their world—or will soon be, after all. So they need to get cracking. And of course they already are. Just look at the terrific work done by the Parkland Florida students who are challenging the NRA in the streets of Washington and across the nation. Consider their more than a little remarkable March for Our Lives protests: an anthem for gun sanity, if there ever was one. Consider their comrades in school safety-- all those young people who staged the National School Walkout.

So it’s plain for all to see: righteous and effective activism is on the rise again in America. But obviously more, much more is required, especially on critical issues like the environment. America’s youth need to weigh in more on issues of war and peace, weigh in heavily and persistently. They need to ask themselves where is their planet is headed? What will it look like by the dawn of the 22nd Century? How can they help shape it, save it, safeguard the destiny of the human race? They need to get to the point where they forge a global consensus on what constitutes an achievable balance between economic growth and environmental sustainability, so that the world not only survives but thrives. They need to figure out what a form of global governance looks like. Nationalism is the enemy of globalism and globalism isn’t going anywhere, so there needs to be an alternative. That’s clear. And that’s their opportunity.

Activism is a generational relay, a continuum of commitment passed hand over hand, from one activist to another, down across the years. And this history of dedication to a cause is a true and meaningful thing because change of any kind of importance takes so very long to accomplish, to achieve. Nevertheless, to be a part of this human chain for change that has the potential to shape history, to strengthen justice, to advance the world at large towards higher human freedoms, is something, well, magnificently worthwhile. Aside from creating art of whatever kind, or serving humanitarian causes generally, I’m not certain what else could be of much higher value or meaning.

And this is especially apparent today, what with the alarming decay in the coherence and credibility of our national political discourse. You know, I’ve often said that we’re experiencing a golden age of NGOs (Non-governmental organizations), of activism, because of the tools of social activism have never been more powerful, more penetrating. I suppose that’s both a blessing and an extraordinarily heightened responsibility because this effectively means that activists have to be that much more deliberative about what they say and how they say it, about the precision of their information, and about how they make their case for change. It’s really a watershed moment for local, national and international change. It’s not a question of whether people can change things; that’s been settled: they can. It’s more a question of how the world is going to change. In fifty years, will people have more rights or less? Will the world be more fair or less? Will the environment be more pristine or not? Will there be peace or chaos?

Are there any personal life events that have inspired you to write? What are they?I think I start less with the personal and more with the the driving theme I’d like to explore, and hopefully make live in some kind of dynamic, sparkling way. In other words, I start on the other side of plot, even character and consider to the heat of the idea first before inventing the rest. It’s just that simple. So in that sense the story, the characters, serve the the theme and premise. Now that’s not terrible organic, is it? Not like it would be if I drew from a more personal experience. Rather, it’s a willful construction borne out of the need to talk about, shout out about something I find riveting. But perhaps the themes I set out to explore are in a sense personal experiences that affect me and drive me to write about them. I suppose they are.

Is there any other book coming up that the readers can look forward to? Is this also about politics or will you explore other genres?Yes, I do have several ideas whispering at me. Naturally, they’re political ideas. The rapid and wholesale disintegration of privacy here, there and everywhere is deeply unnerving and exploring that threat to individual autonomy may merit some quality time. On the other hand, I just might surprise myself and write a delirious love story. Short, dense and searing.

Anything could happen, and very probably will. Part of the joy, of course, if joy is a word that can appropriately get anywhere near alongside the word “writing”, are the surprises that come to you along the muddy way. In a sense, that’s what I’m in it for, the organic surprise. The unearthing of the new idea or setting or expression through a process that I call the organic reveal.

Share Timothy Cooper's interview

Born in Los Angeles, author Timothy Cooper grew up in Washington, DC where he learnt that humor could address and highlight social justice issues. Inspired by Mark twain’s works, Cooper recollects to have written six or seven drafts for “2020 or My Name is Jesus and I am Running for President”. Writer of “World One” which he calls “nuclear” fiction, Timothy decided to become a writer when he was in film school and was 19 years old. Working distinctively for humans rights all across the world, he believes that it is an honorable profession. A pianist, photographer, and a writer, Cooper says choosing which of them he loves most is like choosing a favorite child- impossible. Working on a few ideas for new books to come, naturally political, Timothy believes that the youth can make a change in the world just like it has in the past and continues to believe in his political views and write about them, fearless!